Could Queen Nefertiti’s Tomb Reveal Secrets From Egypt’s Shadowy Past?

She was married to one of the most eccentric pharaohs. But after his death, she may have reigned on her own–as a man. If researchers have found her tomb, what’s inside could change Middle Eastern history.

Every time something is discovered in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings, the whispers begin. Is it the queen? Has she finally been found? They’re asking about Nefertiti, the legendary beauty who was married to one of ancient Egypt’s strangest pharaohs. Her burial site has never been found, and its location is one of the enduring mysteries in Egyptology.

The buzz is now as loud as ever, as scans of King Tut’s tomb indicate there may be hidden chambers behind sections of walls. Questions have inevitably arisen about possible links to Nefertiti, and whether archaeologists will peek behind the walls to find room after room filled with the dazzling grave goods of the long-lost queen.

THE THEORY OF NICHOLAS REEVES

It’s exciting, of course, to speculate about a treasure that could eclipse the wondrous things that came to light when Tut’s tomb was found in 1922. But in the world of archaeology, it’s information, not gold, that’s priceless. And experts are now hoping for something beyond the bling. The list of ancient Egyptian kings, as we know it today, is a work in progress—a compilation made by modern scholars and based on found fragments. Nefertiti’s tomb could hold clues that will help Egyptologists understand a royal succession that’s still unclear.

Here’s what they’ve been able to piece together from Nefertiti’s time:

Early in the 14th century B.C., at the height of the 18th dynasty, a powerful pharaoh named Amenhotep III ruled Egypt for more than four decades. When he died, his son and heir, Amenhotep IV, took the throne. But something caused the new pharaoh to break with tradition in ways that were shocking.

He smashed the temples and statues of a popular god named Amun and began to worship a god named Aten, represented by a sun disk. He moved his capital to a new location in the western desert, a place called Akhetaten, meaning “Horizon of the Aten.” He changed his name from Amenhotep, or “Amun is Pleased,” to Akhenaten, “He Who is of Service to Aten.” And he revolutionized the country’s art, launching a realistic style that depicted him with a flabby beer belly rather than the usually idealized six-pack abs of a young and virile pharaoh.

Nefertiti—which means “The Beautiful One Has Come”—was Akhenaten’s principal wife.

Her second name was Korey/Kori and it is found in Egyptian Cartouches. This is one of the elements that makes one wonder over her (Greek?) ancestry.

There’s no record of Nefertiti and Akhenaten producing a son. But they had six daughters, and we know their names: Meritaten, Meketaten, Ankhesenpaaten, Neferneferuaten Tasherit, Neferneferure, and Setepenre. Like every pharaoh, Akhenaten had more than one wife. One of the minor consorts may have been the mother of the future King Tut, whose original name was Tutankhaten—”Living Image of the Aten.”

One of the desert canyons west of the Nile, the Valley of the Kings holds the burial of King Tut—and maybe Nefertiti, in chambers hidden behind his. In antiquity this was considered a secluded spot. Today the growing suburbs of Luxor shimmer nearby.

TUTANKHAMUN

Did Nefertiti Rule as a King?

When Akhenaten died, Tut didn’t become king immediately. Someone else, a shadowy figure named Smenkhkare, seems to have ruled for about two years.

Could that have been Nefertiti taking on a new identity? Possibly. Nefertiti certainly played the expected roles of an elegant royal wife and devoted mother. But some experts believe that she became her husband’s co-ruler during the latter part of his reign. When he died, she somehow managed to stay on the throne, ruling with all the attributes of a male pharaoh. And she took a new name—Smenkhkare.

New evidence supports the theory that King Tut’s tomb has a hidden chamber, according to experts who this week completed the first-ever radar scanning of walls inside.

We don’t know much about the roles of women in ancient Egyptian society. As far as we can tell, most were anonymous wives and mothers. At the upper levels of society, some performed duties at temples. But the royals played by different rules entirely. If Nefertiti did take the throne and rule as a man, it would have been unusual, yes, and unexpected, surely, but not unprecedented.

If Nefertiti was Smenkhkare, it would make sense for her to be buried in the Valley of the Kings, the great royal cemetery of the 18th and 19th dynasties. She was a pharaoh, after all.

Why Would She Be Buried With Tut?

When Smenkhkare—whoever he or she was—passed on, King Tut rose to the throne. By then Egypt’s spiritual life was taking a 180-degree turn, as the faithful rejected Aten and returned to the traditional god Amun.

Tut’s name was now a liability since it was linked to the heresy of Akhenaten’s regime. It had to change, and fast. And so he became Tutankhamun.

Tut was only eight years old or so. But in time he married one of Nefertiti’s daughters—possibly his half-sister. She too had a name problem. At the start of her life, she was Ankhesenpaaten—”She Lives Through Aten.” And so she too made a switch, to Ankhesenamun—”She Lives Through Amun.”

When King Tut died, after ruling for only a decade, there apparently was no place to put him. Royal tombs often had long passages and numerous chambers, and cutting all those spaces into the limestone cliffs of the Valley of the Kings was a laborious process.

It’s possible that the teenage pharaoh was placed in a tomb that had been started for someone else and was only partly finished. In that case, the void that appears in the recent scan may lead to the rough, working edge of construction.

On the other hand, Tut may have been buried in the tomb of a royal who died before him, someone of his same stature. And if that royal is Nefertiti, it means he was laid to rest with someone who was both his stepmother and mother-in-law.

From today’s perspective, it seems a strange twist of fate. But who knows? In their convoluted, inbred family, Nefertiti and Tut may have adored each other like mother and son and would have been perfectly fine with the idea of spending eternity together, separated by only a wall.

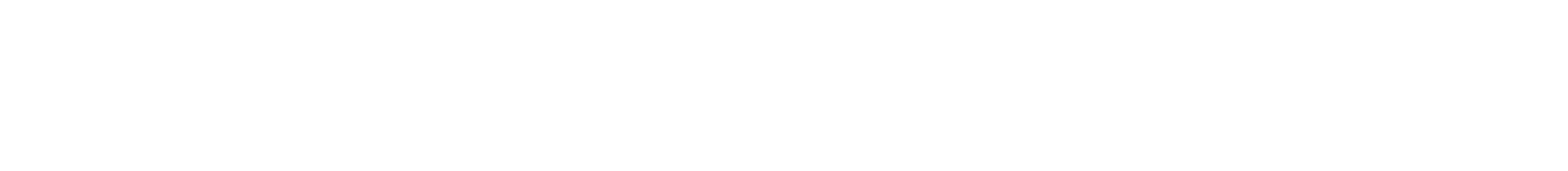

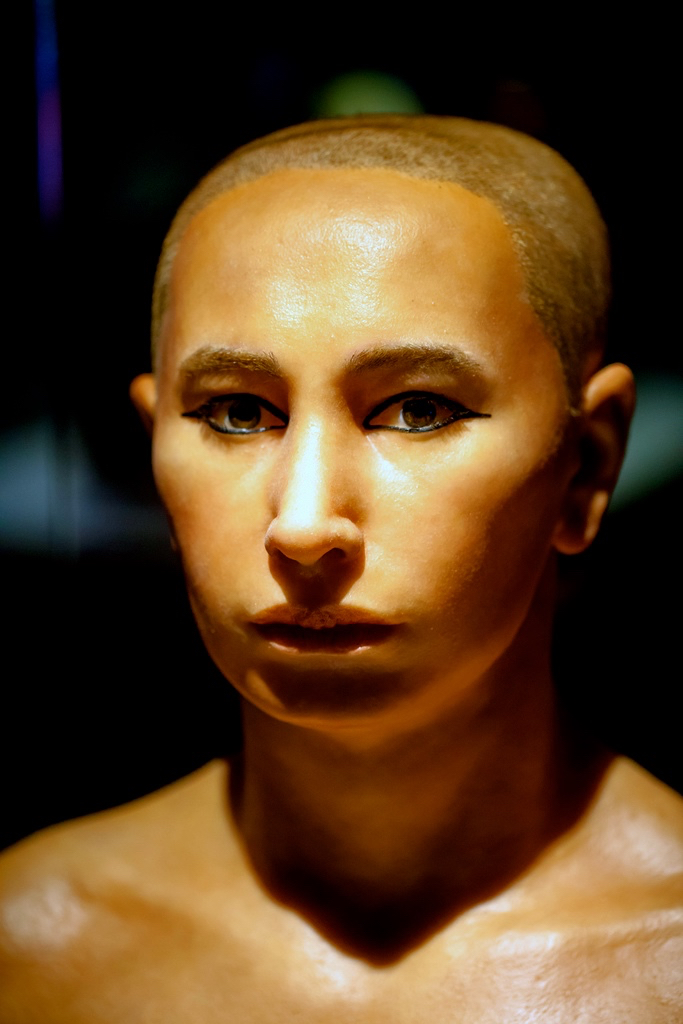

KING TUTANKHAMUN

Ancient Egypt’s most famous pharaoh was the offspring of a union between siblings. Inbreeding may have afflicted him with a congenital clubfoot and even prevented him from producing an heir with his wife, who was probably his half-sister.

Photograph by Kenneth Garrett, National Geographic Creative Commons.

TUT’S WIFE

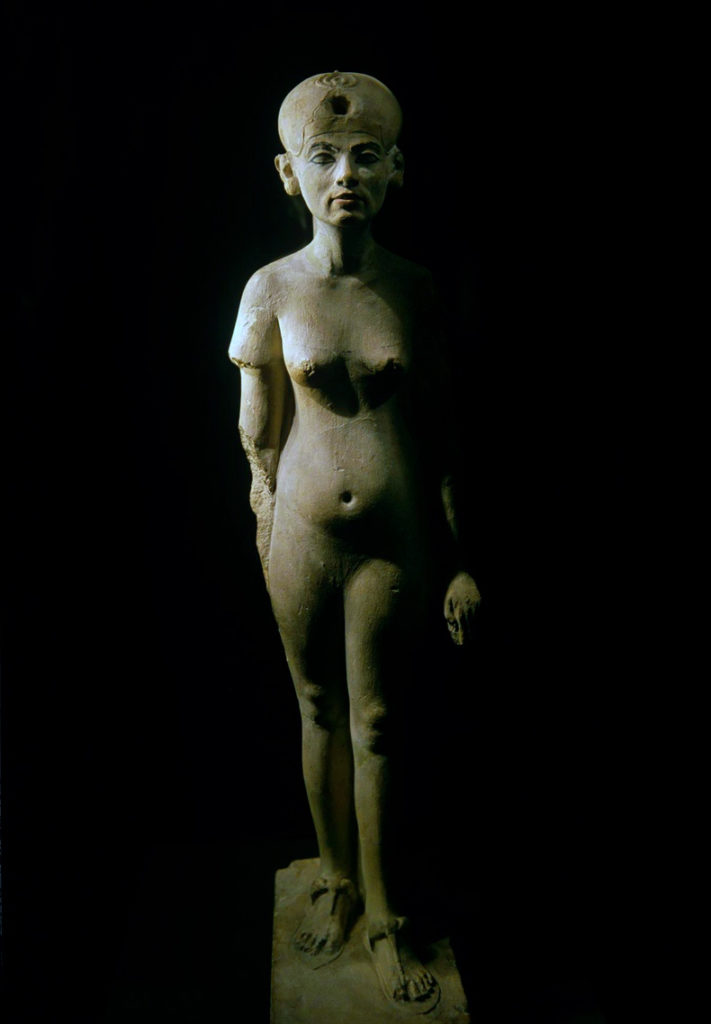

DNA results suggest that this mummy—made headless by vandals—could be the mother of at least one of the foetuses found in King Tut’s tomb. If so, she is likely Ankhesenamun, a daughter of Akhenaten, and the only known wife of Tutankhamun.

Photograph by Kenneth Garrett, National Geographic Creative Commons.

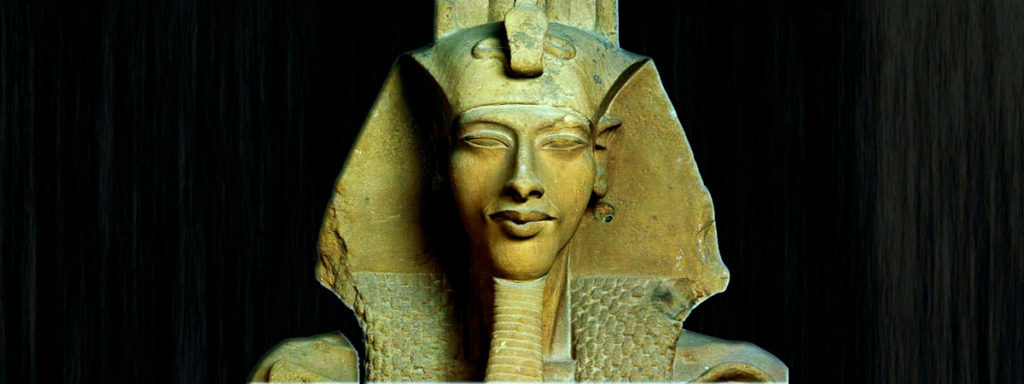

TUT’S GRANDFATHER

Amenhotep III ruled in splendour some 3,400 years ago. His body was found in 1898 hidden along with more than a dozen other royals in KV35, the tomb of his own grandfather, Amenhotep II.

Photograph by Kenneth Garrett, National Geographic Creative Commons.

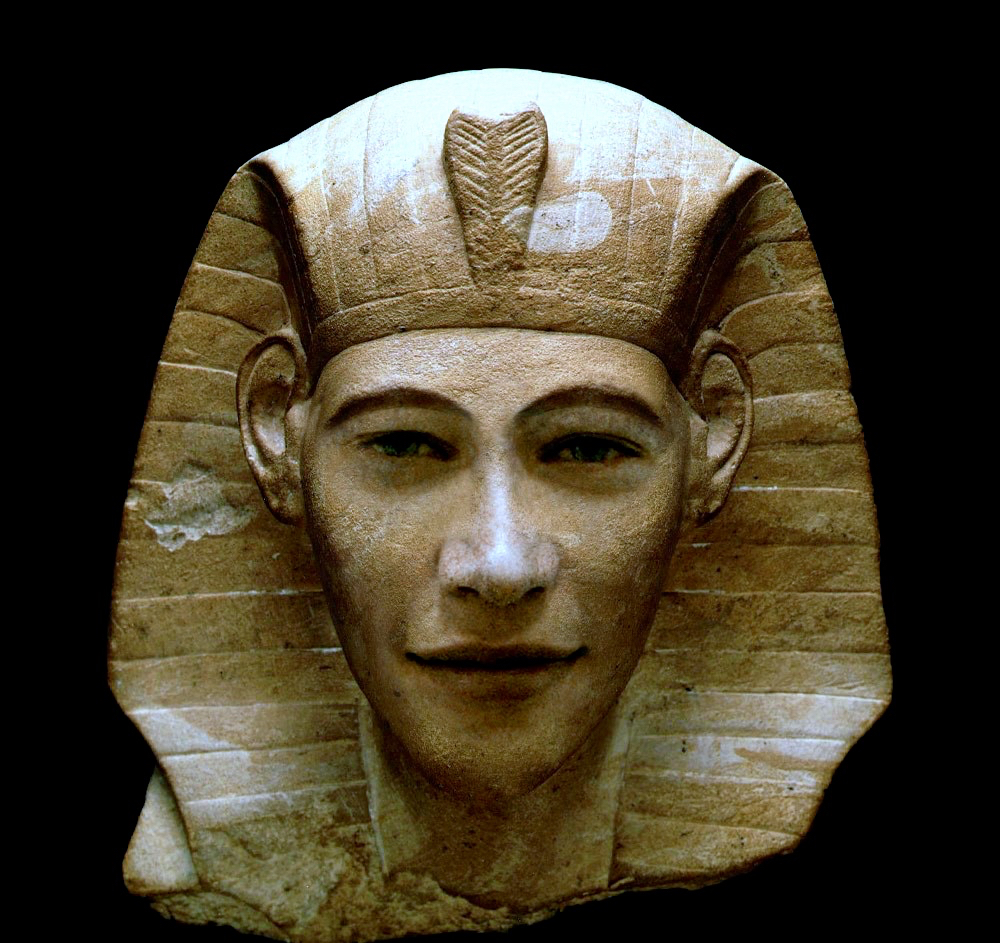

TUT’S GRANDMOTHER

A DNA analysis has identified this regal beauty as Tiye, Amenhotep III’s wife and Tut’s grandmother. She was embalmed with her left arm bent across her chest, interpreted as a queen’s burial pose. Her hair remains intact thanks to Egypt’s arid climate.

Photograph by Kenneth Garrett, National Geographic Creative Commons.

TUT’S FATHER

This badly decayed mummy was discovered in 1907. Royal epithets on its defaced coffin suggested it might be Akhenaten, the heretic pharaoh who forsook the gods of the state to worship a single deity. DNA confirmed the mummy to be Tut’s father.

Photograph by Kenneth Garrett, National Geographic Creative Commons.

TUT’S MOTHER

According to DNA tests, this mummy, known as the Younger Lady, is both the full sister of Akhenaten and the mother of his son, Tutankhamun. The Younger Lady is probably one of the five known daughters of Amenhotep III and Tiye.

Photograph by Kenneth Garrett, National Geographic Creative Commons

TUT’S DAUGHTERS?

A foetus of at least seven months’ gestation (right) was found in Tut’s tomb along with a tinier, more fragile foetus. One or both may have been his daughters. Nested coffins (left) contained a lock of hair, perhaps from Tut’s grandmother Tiye.

Photographs by Kenneth Garrett, National Geographic Creative

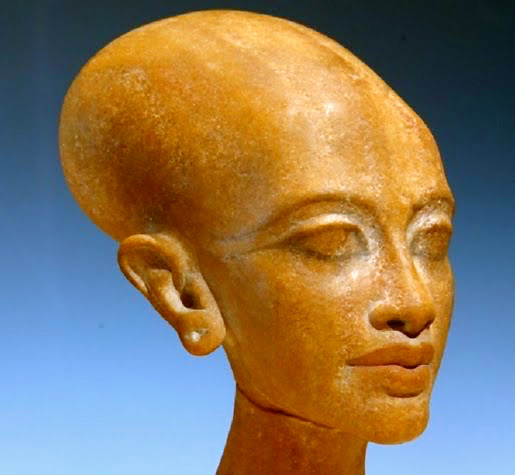

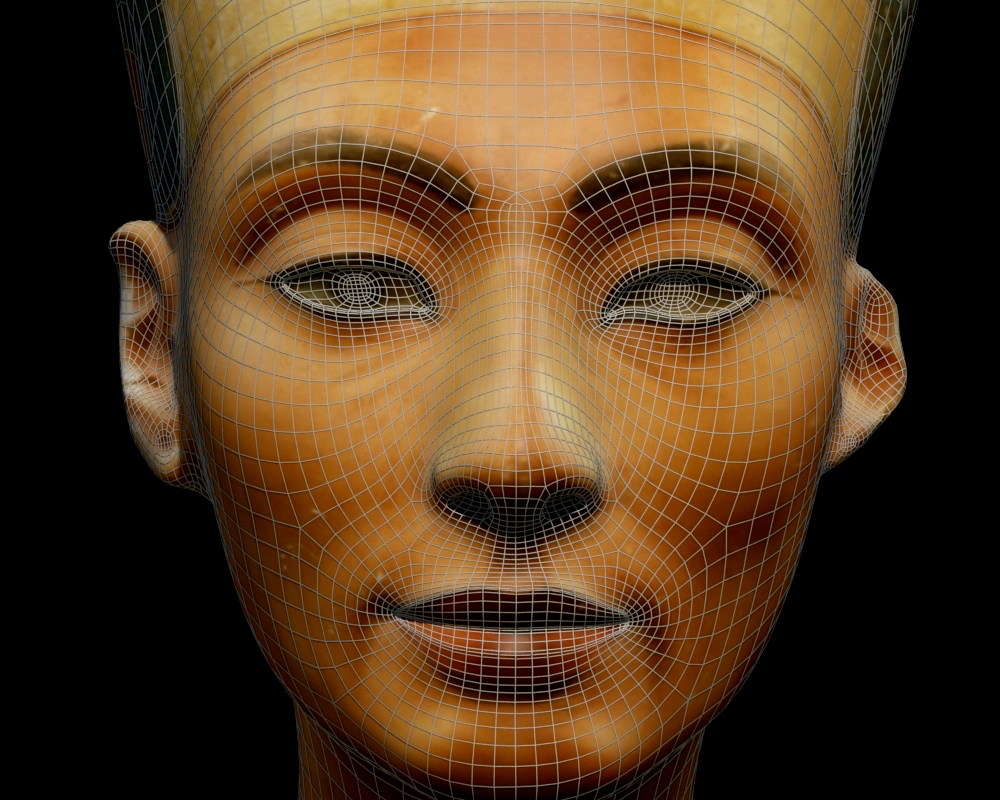

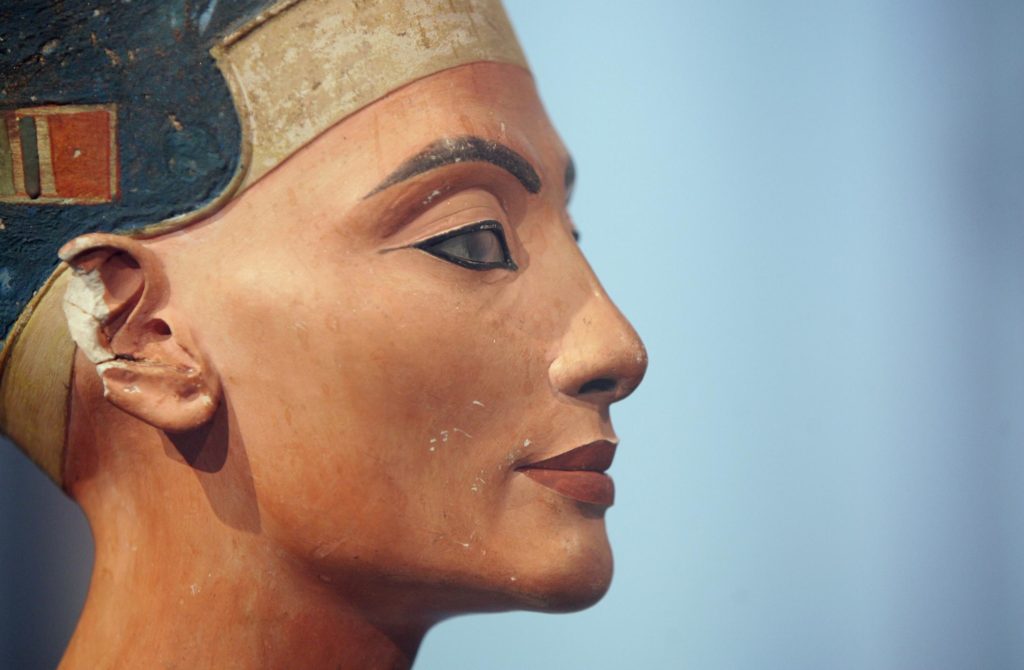

The now-iconic bust of an elegant, beautiful Nefertiti was discovered in 1912. It lay in a royal sculptor’s workshop at the archaeological site of Amarna, the ruins of the capital city built by Nefertiti’s husband, Akhenaten.

THE TOMB OF TUTANKHAMUN

AKHENATEN

NEFERTITI

TUTANKHAMUN

NEFERTITI

NEFERTITI

TUTANKHAMUN

NEFERTITI

NEFERTITI

TUTANKHAMUN